Putting myth to use in contemporary times: Tantalus within today’s ecology

Athens’ famous Acropolis, the city’s most prominent hill, served as the primary water source in ancient times. According to myth, it was Poseidon, the god of the waters and the sea, who created the first well on this hill with his spear. It became an important symbol of the city’s connection to its mythology, especially as various springs and wells on the hill were used by inhabitants for drinking water and religious ceremonies. In Alexandria, we find a resonance of the myth through Poseidon, to whom the mythical Pharos (the Lighthouse of Alexandria) was dedicated.

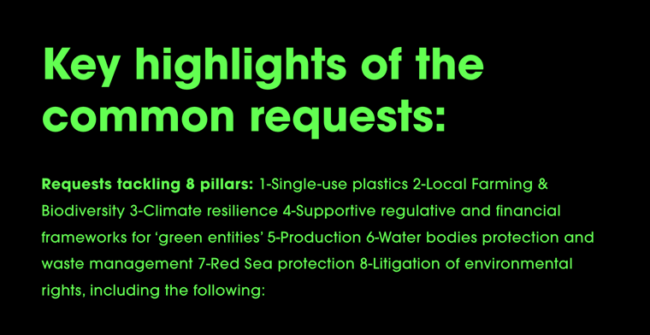

In reinterpreting these mythologies, the aim is to draw parallels between the current ecological crisis and ancient literature in the political and legal circumstances of today’s Mediterranean and beyond. We have been endlessly exploiting our waters for years. We are eating poisoned fish. We are swimming in water contaminated with plastic. What will be the impact in the coming years if these unethical, non-ecological, and unsustainable conditions persist? By abusing our land and our sea, won’t we be punished just as Tantalus was. Many of the challenges facing humanity today revolve around our relationship with water, whether we are talking about the waters surrounding land or the water sustaining these lands. A focus on the Mediterranean Basin – the origin of Greek mythology – could encompass other seas, oceans, and lands, all connected through water. Water, in fact, travels freely, interchanging from one side of the Mediterranean to the other, through passages that myths have invested with a universal aura. I aim to explore the aquatic bodies of the dirtiest sea on the planet and the cycles associated with them: of birth and death, of ecology and waste, all sharing the same binder, tie, or vehicle for their existence – water.

How would the legal and administrative configurations of today’s Mediterranean countries — with their divergences between European and non-European states, as well as across Asia and Africa — apply to other geographical contexts and diverse aquatic bodies? We usually govern the sea through land-based divisions and regulations, but what if the geography of the sea itself ordered the surrounding territories — as in the Mare Nostrum context of the Roman Empire?

Grounding my perspective in an environment I know intimately, the center of the world as I perceived it in childhood, I have been exploring narratives drawn from both reality and mythology. This exploration unfolds as a conversation across time and place, extending also to the regions I encountered later as an adult. What conclusions might we reach if we examined more closely how mythical and metaphorical lessons can be applied in today’s world?

Myths, in this regard, endure beyond geography and history, as their lessons have a global reach. Tackling a problem with global implications – namely, the ecology of water – I turn to the artistic imaginary to bridge the gap between fantasy and reality.

Having grown up on the shores of the Mediterranean, I am fascinated by the dynamic between heroes and gods in Ancient Greek mythology: the suffering inflicted for transgressions is at the foundation of our understanding of civilization. Myths endure beyond geography and time; they are quintessential lessons with a global reach. What particularly interests me is revisiting these myths and giving them a contemporary explanation. The dialectic of crime and punishment, which is at the core of mythology, along with ideas of climate and human justice worldwide, converge in the Greek myth of Tantalus.

To question our relationship with heritage and memory, I have often resorted to fiction, as much as to mythology, to propose explanations and unveil possible links, engaging in a reinterpretation of art history, an instrumentalization of archaeology, throughout an anthropological approach, basing the narrative on the analysis of laws and geopolitics. The ultimate aim is to create a bridge to the past and bring these issues to the contemporary audience, while bridging the collective history to the present experience the audience is exposed to In this way, contemporary problems become more atemporal.

My overall methodology consists of conducting extensive research, which I later use to develop a narrative thread in order to reinterpret the myth and give it a contemporary, relatable meaning. For instance, who is the Sisyphus of Choreography of a Woman and a Stone, who escaped death twice, if not any Lebanese person who survived the Beirut explosion, and before that, the 2006 war? Who is the Prometheus of Secrets of the Infinite Sea, if not a Syrian migrant fighting for a place on land and in the waters, having his liver metaphorically eaten every day, only for it to grow back each night – on hope? Who is Tantalus, if not any Mediterranean, or any inhabitant of a marine environment, living on the border of the most beautiful and rich sea on the planet – yet the dirtiest, the most inaccessible one?

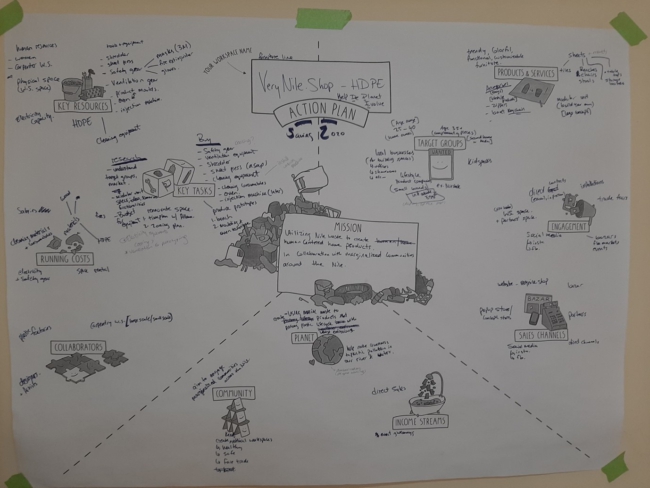

While adjusting and reevaluating mythical narratives, I strive to adapt them to the evolving contexts we currently live in or witness. They serve as a reading of the humanist values I fundamentally believe in and become the stage for my own convictions. This is how handling the research process like a legal case would look: What, in today’s world, would bring the myth of Tantalus as a strong metaphor about our ecologies beyond experts’ reports and scientific analysis ? ? How can I defend the point of view of the actuality and foundation of a myth in 2025?

In other words, it is about how to tackle a subject on stage in the same way I do when confronted with a legal question. First, looking at the (historical) facts; second, pinning down clear links and identifying unknown elements; third, applying the (ancestral mythical) law to finally solve “the mystery.” Here I am, becoming an artist: I defend, I plead. Therefore, in a way, every text of my lecture performances, which all happen to be monologues, becomes another “lawyer’s defense.” They stand as pleas, as arguments of an attorney, embedded with poetic images and sounds, engaging the audience as witnesses in a court. Is the evidence I show on screen fake or real? Are these sounds synthesized or natural? This is the difference between theater and performance. In theater, one can fake an action; in performance, the action is real. And when my audience sees blood on my screen, that is real blood. That is when I run with a stone, and that stone really breaks my back (Choreography of a Woman and a Stone, 2021). Or when I sit with a cow’s liver and smell its putrid odor (Secrets of the Infinite Sea, 2022). The sounds I use are compositions made on my request, based on written notations I present to the sound designer. The latter then composes and orchestrates the sounds according to my discursive expressions. This also does not prevent me from twisting some elements, playing the devil’s advocate – or whomever I choose to campaign for – whether by adding fiction to the truth, sometimes with nihilism, and sometimes through a hidden agenda.

On November 19, 2024, the haka, according to the Merriem Webster, “a traditional Maori dance that is typically performed in a group and involves rhythmic usually vigorous movements (such as foot stamping, body slapping, and swaying), intimidating postures and facial expressions, and loud chanting and that is expressive especially of pride, strength, and unity” performed in New Zealand’s parliament transcended political debate, embodying ancestral wisdom and resistance. Led by Te Pāti Māori MP Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke, this act protested against a controversial bill seeking to redefine the Treaty of Waitangi, the 200-year-old founding agreement between the Māori and the British Crown. The haka united lawmakers and spectators, halting parliamentary proceedings and proving that cultural heritage can resonate more powerfully than legislative discussion. Cultural heritage, steeped in ancient myths and rituals, holds a profound capacity to address contemporary environmental emergencies.

Myths, far from being mere relics of the past, are enduring vessels of collective memory, carriers of knowledge—often related to nature—and bridges between generations. They encapsulate humanity’s connection to the landscapes and values that have shaped societies. The Babylonian creation myth Enuma Elish, for example, reflects the balance between chaos and order. Apsu, the freshwater deity, is driven to silence the younger gods, whose activity disrupts his peace. His actions unleash conflict, ultimately leading to the establishment of a new world order. This tale mirrors environmental struggles today, as the scarcity of water in ancient Mesopotamia resonates with the desertification of the Euphrates region. The work of the World Opera Lab is a perfect example. The group’s work shows how across cultures, similar themes recur. Rituals invoking divine intervention for rain, such as the “Brides of the Rain” ceremonies, are found in regions as diverse as Kurdistan, Zambia, Morocco, and Bulgaria. These shared narratives underscore a universal awareness of humanity’s dependence on natural cycles. They also demonstrate the potential for myths to serve as tools for connection, highlighting the common ground between distant geographies and histories.

Myths, far from being mere relics of the past, are enduring vessels of collective memory, carriers of knowledge—often related to nature—and bridges between generations.

Rituals, deeply symbolic and communal, possess untapped potential as advocacy tools in environmental campaigns. Their integration into modern efforts can create emotionally resonant and culturally grounded strategies for raising awareness. The haka, for instance, embodies not only resistance but also collective strength and unity. Such rituals, when adapted thoughtfully, could inspire communities to rally around environmental causes. Participatory reinterpretation of myths in contemporary artistic and social projects fosters collective ownership of both cultural heritage and environmental responsibility, bridging the past with the future. This process transforms myths from static narratives into dynamic, living traditions that engage with present challenges.

Heritage itself must be understood as an evolving practice rather than a fixed object. It is not merely something to preserve but something to reimagine in the service of contemporary needs. Recognizing the etymological link between “agriculture” and “culture” reveals the intrinsic connection between cultivating nature and fostering human identity. This perspective underscores the role of heritage in promoting environmental preservation. Both rural and urban environments hold equally significant narratives. Even in the most industrialized cities, cultural heritage thrives in the form of stories, rituals, and practices that reflect humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

The distinction between tangible heritage, such as monuments, and intangible heritage, such as oral traditions and rituals, must dissolve to fully realize the potential of cultural heritage in addressing ecological challenges. Myths, as one of the earliest forms of law, provided order and connected communities to the natural world. Their lessons about balance, justice, and sustainability remain relevant as humanity grapples with environmental crises. By reinterpreting these narratives, societies can craft legal and social frameworks that align with ecological realities.

Myths and rituals, therefore, are not merely remnants of ancient cultures but active forces that can guide present and future generations. They invite us to reconsider the relationship between humanity and nature, offering a path toward more sustainable practices. Cultural heritage, shaped and reshaped through engagement and reinterpretation, becomes a dynamic process that informs our understanding of justice, resilience, and collective responsibility. In this way, it is not only a bridge to the past but also a roadmap for a sustainable and equitable future.

![Screenshot van VeryNile's Instagram-pagina met de sloganمترميش في النيل يا منيل [‘Gooi het niet in de Nijl, schurk!’]](https://www.hetgrotemiddenoostenplatform.nl/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Nile2-650x435.png)