De confronterende spiegel van het verhaal van Alexandrië

Journalist Cousin neemt de lezer mee naar ‘zijn’ Alexandrië, over de corniche (boulevard), langs de pleinen en door de smalle steegjes. Het is knap hoe hij het alledaagse van de stad verweeft met grote maatschappelijke thema’s. Migratie, mondiale ongelijkheid en klimaatverandering komen aan bod, vaak vanuit het perspectief van veelal jonge Alexandrijnen.

Plekken om te slenteren

En deze grote thema’s krijgen door die lokale blik soms net een andere kleur. Het verstikkende effect van het Sisi-regime op het maatschappelijk middenveld is algemeen bekend. Maar voor mij was veel minder duidelijk dat dit ook zijn uitwerking heeft op de fysieke publieke ruimte. Overal in de stad zijn bouwprojecten gaande, met het leger als grootste projectontwikkelaar en de openbare ruimte als grote verliezer. Parken, pleinen en zelfs de corniche worden volgebouwd met nieuw panden, cafés, restaurants en hotels. ‘Plekken om te slenteren, plekken die uitnodigen tot een spontane samenkomst en die, wie weet, tot verzet zouden kunnen leiden, worden weggehaald of afgesloten.’

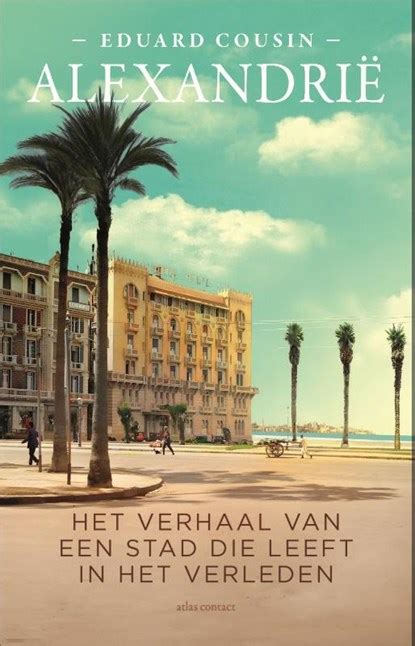

Zo neemt Cousin ook mij mee terug naar Alexandrië, de stad die mijn kennismaking was met Egypte en met het Midden-Oosten. Mijn eerste nacht in Alexandrië bracht ik door in het hotel dat op de omslag van zijn boek prijkt. Nee, niet het chique Hotel Cecil, dat was te duur voor de student die ik toen was. Maar het gebouw ernaast, Hotel Acropole, met een even mooi uitzicht over het Saad Zaghloulplein. Een paar maanden Alexandrië hebben mij een levenslange interesse in deze stad bezorgd. En een even lange fascinatie voor de Middellandse Zee als centrum van een gedeelde EuroMediterrane ruimte. Een historische constante, die we op dit moment alleen totaal verloren zijn.

Nostalgie en weemoed

De zee als verbinding met Europa, de Europeanen in Alexandrië en de veranderingen die zich daarin voltrokken, vormen de rode draad door het boek van Cousin. Hij geeft volop ruimte aan de bijna clichématige manier waarop – zeker in het Westen – naar Alexandrië wordt gekeken. Hij heeft het over de stad van nostalgie en weemoed, en over ‘de welhaast mytische status van deze kosmopolitische stad’.

Cousin blijft daar niet in hangen, en dat is voor mij de kracht van zijn boek. Hij houdt zichzelf en ons als lezers een spiegel voor, en confronteert ons met een hardnekkige eurocentrische houding. We cultiveren een Alexandrijnse geschiedenis waarin Europeanen een hoofdrol spelen en waar de Egyptenaren uit zijn geschreven. Waarbij we gemakshalve vergeten dat Alexandrië lange tijd een ‘gekoloniseerde stad’ was, met een elite van Europeanen en met Egyptenaren als ‘gemarginaliseerde tweederangsburgers’. En waarbij we de teloorgang van de stad hebben gekoppeld aan het vertrek van de Europeanen en de komst van de Arabieren. Terecht stelt Cousin de vraag: ‘Wie bepaalt wat beter is, wie heeft het recht op het waardeoordeel? Is de stad vervallen, of veranderd?’

Zijn spiegel voelt oprecht, omdat Cousin ook zelfkritisch is, direct al in zijn inleiding. ‘Ikzelf heb Alexandrië altijd als mediterrane stad gezien. Heeft dat niet ook te maken met het feit dat ik bij Alexandrië de associatie met de oude Grieken en Romeinen heb? […] Heeft het te maken met het feit dat de architectuur in de stad me doet denken aan de steden in Italië en Zuid-Frankrijk waar ik met vakantie ging? […] In andere woorden, maakt dat wat je zou kunnen omschrijven als het Europese gezicht van de stad, dat ik haar als mediterraan beschouw, en daarmee als onderdeel van mijn wereld?’

Uiteindelijk heeft Cousin een glasheldere boodschap: onze weemoedige blik op Alexandrië leunt op ‘oriëntalistische ideeën over een beschaafd, geletterd en verlicht Westen versus een onbeschaafd, barbaars Oosten’. Rake observaties, die ook een ander licht werpen op mijn nostalgische gevoelens over Alexandrië zoals het ooit was.

Verlies van hoop

Zo koppelt hij het verhaal van Alexandrië aan een veel groter vraagstuk: hoe verhouden Europa en het Midden-Oosten zich tot elkaar? Hoe verhoudt het Westen zich tot de rest van de wereld? Cousin verwijst naar de Arabische existentialisten, die in de jaren vijftig en zestig pogingen deden om een nieuwe, postkoloniale identiteit vorm te geven, gebaseerd op emancipatie, burgerschap en individuele vrijheden.

De morele klap van de nederlaag in de Zesdaagse Oorlog, en het gebrek aan Europese steun voor de vrijheid van de Palestijnen, maakte hier een einde aan en had grote gevolgen voor Alexandrië. ‘Wat betekende het Alexandrijn te zijn in deze post-koloniale wereld na 1967? Wat is de positie van Alexandrië zonder verbindingen met de andere kusten van de Middellandse Zee? Zonder blik op de toekomst, zonder nieuw verhaal, was er eigenlijk maar één optie: terugkijken naar het verleden, naar het oude verhaal. Dit is de bron van de nostalgie naar de kosmopolitische stad. Het verheerlijken van dit verleden is een antwoord op het verlies van hoop op een toekomst na 1967.’

En daar ziet Cousin directe parallellen met vandaag. Alexandrië is de stad van de zee, van oudsher op allerlei manieren verbonden met de andere mediterrane kusten, en daarmee ook met Europa. Het is Europa dat van die binnenzee een harde buitengrens maakt. Door muren en hekken te bouwen. Maar zeker ook door de westerse positie ten aanzien van Gaza, de bijna onvoorwaardelijke steun aan Israël en de ongelijke menselijke standaarden die worden gehanteerd. Cousin is somber maar realistisch: ‘Al mijn pogingen in dit boek om te ‘verbinden’ zijn futiel zolang we in het Westen niet dezelfde waarde hechten aan een gedood Palestijns kind als aan een Israëlisch kind, of evenveel treuren om een Palestijnse gedode journalist als om een westerse journalist.’

Zo trekt Cousin het verhaal van Alexandrië, van de stad die leeft in het verleden, in één ruk naar het heden. En houdt hij ons daar de spiegel voor die misschien wel het pijnlijkst is.

Eduard Cousin, Alexandrië. Het verhaal van een stad die leeft in het verleden. Atlas Contact.