De Corniche in Alexandrië. ©Heba Elhanafy

Blue and Green going hand in hand: that’s how to save the coastal zones of the Middle East

The MENA region boasts thousands of kilometers of coastline. Where land and sea interact, that's where the coastal zones are. They have distinct maritime cultures and contain some of the most productive and valuable habitats on earth. They are often preferred areas for population and for many sectors of society, such as the military, commerce, infrastructure, and industries.

The management of these coastlines affects the environment of millions of people. Actions taken on land impact the state of the sea. So, from privatized beaches to polluted sea water: blue and green go hand in hand. This connectedness of land and sea was the topic of a Green MENA Network online meeting with two speakers; Dr Manal Nader from Lebanon and Heba Elhanafy from Egypt. They enlightened us on the importance of having an integrated coastal zone strategy.

Take the case of Lebanon. Eight percent of the country consists of coastal zone, while fifty-five percent of Lebanon’s population lives there and seventy percent of the country’s industrial zones are located at the coast.

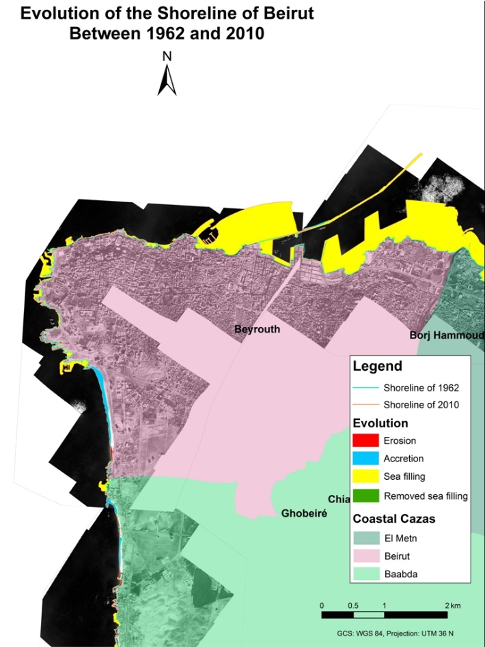

Dr. Manal Nader, director of the Institute of the Environment, University of Balamand, Lebanon explains how the Lebanese coastline is evolving. A study found that it is seriously affected by sea filling and erosion. The part of the coastline that is sandy or consists of pebbles (20% of the total 220 km), has seen an erosion of 2,5 million square meters. ‘What is also extremely worrisome is that we have more than 8 million square meters of sea filling in the remaining 80%. Rubble that has been dumped into the sea to create more land. Such fillings change currents and nutrient regimes in the sea.’

Or take the case of Egypt. Heba Elhanafy, an urban planner and architect, researched how the Corniche Road in the coastal city of Alexandria affected the shore and especially the life of Alexandrians. The road was constructed by the British colonial regime in 1935 to transfer goods along Alexandria. From being just a rocky shore the coast started to have different functions. People began using the waterfront as a public space, and there were casinos and private businesses. After the establishment of the Republic of Egypt in 1952 until the late nineties, the waterfront started to become a real middle class getaway for people of different social groups. There still was a balance between public and private beaches. Elhanafy: ‘For Alexandrians, this historical access to the Mediterranean became their number one identity.’

In 1999, a vast corniche expansion was built in the water. The four-lane road became ten to sixteen lanes wide. A first impact study showed that the expansion affected marine life. ‘We used to have a thriving turtle population that I only hear of because during my time it was gone,’ says Elhanafy. Other effects were the loss of nine public beaches and the overtaking of public space by privately owned constructions. ‘Today, the whole waterfront is filled with dense construction. There is a very small percentage of the coast that is beach, and for all of them, you have to pay to get in. The very little public space that still exists is intensively used by locals, even if they have to sit behind a fence.’

Integrated Coastal Zone Management

Both cases make clear that the shared interest from different sectors and stakeholders easily leads to friction. Coastal areas are controlled by several agencies that often do not coordinate with each other. Nader: ‘In addition, we see that there is minimal coordination between private enterprises and NGOs, while they should actually work on a common agenda, and realise that a destroyed coastline is bad for everybody.’

For this reason, Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) was brought into life, a conceptual approach that brings stakeholders at different (intergovernmental, national, local) levels together, to develop integrated strategies. But still, as Nader explains, ‘it all comes down to the quality of governance, as ICZM programs are extremely complex: they are multi-sectoral and seek to integrate and coordinate activities at political, legal, and managerial levels.’

In Lebanon, the ministry of Environment is responsible for biodiversity. The Ministry of Agriculture is responsible for fishery. The Ministry of Transport is mandated over the maritime public domain. The Ministry of Tourism, of course, is responsible for the tourism sector, as the Ministry of Defense is for security and borders (which are also in the sea). ‘They all have to reach agreement on what is to be done in the coastal areas. That is quite a challenge.’ In other countries in the region, the situation is not much easier. ‘As far as I know, integration has not been reached anywhere around the world. Laws are not being passed, and ministries hold tight control of their mandates.’

One of the challenges is to balance between public and private interests. Elhanafy: ‘For me, the role of the public authorities is to protect public interests. Unfortunately, the authorities in Alexandria are protecting only a slice of the community, a certain type of public: those who can afford to pay to enjoy the sea.’ She compares this with other waterfront developments around the Mediterranean. ‘In Barcelona or Valencia, there is a balance between commercial and public access.’

Coastal Zone management is about protecting habitat. The Institute for the Environment identified sites for protection in Lebanon, based on their ecological and cultural values. ‘We found that all cities on the coastline are at risk of sea storms or other forms of environmental stress.’ In Lebanon, there are now a number of marine protected areas (like Nakoura, Byblos and the Raoucheh cliffs and caves off the coast of Beirut) for which there is a national strategy. There are deep sea caves that need protection, especially those that the oil and gas industry is picking up, which is a huge risk. On top of that, climate change impacts the vulnerable life and natural balance at all coastal zones. Sea levels rise, destruction of coralline reef due to exploitation and rise in temperatures, intensifying and higher frequency of winter storms.

Governments responsibility for long term planning.

It is important that governments strategize for the coastlines over the medium to long term, instead of looking at short-term gain. So far, short-term development is mostly the norm at the coastlines of the Mediterranean, as well as at the Red Sea coast, and with the Saudi Arabian development of projects like the NEON project. The same holds true in Alexandria, where plans exist for expanding construction in the sea. Besides the environmental problems related to such building, the plans ignore the very real possibility of Alexandria drowning in the near future due to rising sea levels. Instead of working to protect people living near the sea, authorities and the private sector still seem to go for short term money making.

Nader explains how authorities should consider both the local and the regional effects of developments. ‘The government should do a lot. It should stop dam building. Sediments that replenish beaches come from the floods of rivers. We in Lebanon suffered from the building of the Aswan dam, because the Nile used to pump a lot of sand into the sea, that used to be carried by the sea up to the Gaza – Israeli coastline and zigzag up to us. Those sediments are now trapped behind the Aswan dam. We don’t know what is going to happen with the Ethiopian dam. And temperatures already started rising when the Nile was not allowed to flood anymore. We can also see that erosion on the Egyptian coastline is huge. A few years ago a whole temple of Cleopatra rose up, due to erosion. It was covered by sand, and then again uncovered by erosion. Which means that we see sea levels rising and falling, which is a natural process, but it usually takes a very long time.’

‘Governments should take the interaction between land and sea into consideration. We should stop messing around with the coastline, stop building marinas, stop sea filling, stop looking at quick economic gain as the main approach of our policies. We should use precautionary approaches and think what will happen in the future, with all of the knowledge that has been acquired overtime.’

The role of citizens

According to Nader, citizens should play the main role in deciding how the coastal zones are to be managed. After all, they are the beneficiaries of any government policy. But they cannot go by instinct on quick gain and quick consumption. ‘A collective consciousness needs to be developed, and we see this happening in some areas, for example in the coastal town of Byblos (Jbeil). There, people are starting to agree with us that protecting their coastline is beneficial for them from a touristic perspective, a money-making perspective, but also for sustainability, and for saving on costs on infrastructure or damages. So, citizens have a fundamental role in rejecting certain things. I can do the studies, we can do webinars, but it comes down to the citizens.’

In Alexandria, in spite of the fences, citizens do what they have been doing for hundreds of years: claiming their right to the sea. With a local NGO and the Oecumene Studio, Elhanafy conducted a workshop early this year with youth from different backgrounds on how to increase accessibility to the sea. ‘There are those who go cycling at the sea, the runners, the fishermen who have seen the number of fish depleting.’ In August, they will launch a platform that unites and engages all these people and their activities on the waterfront, to advocate together for more public access and integrated development. Hopefully, they can collectively do what the government fails to do so far: protect the coast and secure a future on land. Because green and blue go hand in hand.

You can watch the recording of the our online event on our Youtube channel.

Share this post via